When Help Is Hours Away: The Top 7 Essential Wilderness Medicine Skills

Wilderness MedicineWhen we venture into the backcountry, whether it’s a day hike in a nearby forest or a multi-day expedition into remote terrain, we knowingly trade comfort and convenience for solitude, challenge, and a deeper connection with nature.

This is a trade-off that comes with a conscious decision to expose ourselves to a higher-than-normal level of risk. Backcountry travel increases our chances of experiencing injury and illness while decreasing our accessibility to nearby basic or emergency medical care.

Mitigating this heightened risk requires improving our wilderness medicine knowledge and skills, something we help people do here at The National Center for Outdoor Adventure & Education (NCOAE). Our Wilderness Medicine and Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) courses cover everything from scene size-up and patient assessment to providing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), treating wounds and fractures, and successfully evacuating patients from remote wilderness areas.

As experts in the field of wilderness medicine, we often find ourselves discussing what we believe to be the most essential wilderness medicine skills. Here, we present our top seven, in no particular order. These are skills that we think all of our students should possess before venturing into the backcountry.

1. Scene Size-Up and Patient Evaluation

Every wilderness medicine event should start with a scene size-up and patient evaluation, which consists of the following three components: (more…)

Words Matter: Speaking the Same Language in Wilderness Medicine

Wilderness MedicineLanguage provides a foundation for human progress. Having a common language enables us to communicate, collaborate, and coordinate our efforts in able us to achieve more together than any of us could possibly achieve on our own. It allows us to organize our thoughts and solve problems collectively.

It’s when we’re not speaking the same language, or we have a different understanding of the terminology being used, that chaos ensues. Take NASA’s Mars Climate Orbiter (aka Mars Surveyor ’98 Orbiter), for example. Launched on December 11, 1998, the spacecraft was lost because NASA used the International System of Units (metric), while the company that built the spacecraft, Lockheed Martin, used the United States customary units (imperial). That simple miscommunication caused the Mars Climate Orbiter to enter the Martian atmosphere on September 23, 1999, at the wrong angle and disintegrate.

As practitioners of wilderness medicine, outdoor educators and others can learn valuable lessons from that story. After all, successful treatment outcomes often require close communication, collaboration, and coordination among treatment providers. Having a different understanding of the same terminology can result in serious negative consequences. This is especially true in life-threatening situations where the space between life and death can be as narrow as a razor’s edge. In these situations, using a common language can save lives.

In this post, we explore wilderness medicine terminology that’s a common source of misunderstandings. By increasing your awareness of how these terms are often used and understood, you can ensure that you and other members of the treatment team are communicating clearly and precisely.

Recognizing Terms That Can Be a Source of Confusion

Communication is so important that EMT textbooks often include an entire chapter or appendix on medical terminology. These terms and their definitions ensure clarity on everything from (more…)

Just the Facts: Recognizing the Importance of Reporting Accurate Information in a Wilderness Emergency

Wilderness MedicineIn the movie Die Hard 2, hero John McLane, played by Bruce Willis, receives a fax at a car rental kiosk at Dulles International Airport in Washington, D.C. informing him of the identity of a suspect. The agent behind the desk, who’s been flirting with McLane through the entire scene, says, “Hey, I close in about an hour. Maybe we can go get a drink?” McLane smiles coyly, points to the wedding ring on his finger, and replies, “Just the fax, ma’am. Just the fax.”

McLane’s line is a reference to the old TV show Dragnet, where the main character, Sgt. Joe Friday, would remind rambling or opiniated witnesses to stick to the facts by saying, “Just the facts, ma’am [or sir]. Just the facts.” That straight-forward statement can serve as a reminder for wilderness medicine providers when we’re responding to accidents or emergencies in remote settings.

In wilderness emergency medicine, collecting and reporting the facts can determine the difference between a positive and a negative outcome, or even between life and death.

Recognizing the Challenges of Reporting Accurate Information in Wilderness Medicine

In wilderness settings, the potential for communicating inaccurate information increases due to several factors, including distance, time lags, layers of patient care providers, and unreliable communication channels, including the absence of cell phone connectivity. First responders frequently face the daunting task of gathering information from people in stressful situations under challenging and changing conditions. In our wilderness medicine course, we teach about the importance of accurate information.

In addition, location information can be difficult to obtain and communicate. Even in an urban setting, first responders can have trouble distinguishing between similarly named roads, such as Bear Hollow Lane and Bear Hollow Road, or roads that have multiple names. In the wilderness, determining and communicating a specific location becomes even more challenging when certain ridges, pitches of a rock climb, or similarly named streams come into play.

Providing accurate and comprehensive information is important for several reasons, including the following: (more…)

Managing Fatalities in Wilderness

Wilderness MedicineIn the safety and comfort of the modern world, we often forget that the natural world can be a dangerous, unforgiving, and uncaring place. For many of us who love wilderness and the backcountry, that’s large part of its attraction.

We choose to explore areas where some fear to go, and we participate in activities that may straddle the line between the safe and perilous. But we do so, backed by best practices and training in wilderness risk management.

Mountaineering, rock climbing, and whitewater rafting can be dangerous undertakings, but even a leisurely hike through the backcountry carries risk. Wilderness emergency examples include entering an area teaming with unpredictable wildlife, crossing paths with a venomous snake, getting swept up in a flash flood, or encountering other unpredictable dangers.

Here at The National Center for Outdoor & Adventure Education (NCOAE), we take many precautions to mitigate the risks. Education, training, planning, and preparation can all limit the risk of injuries and preventable illnesses, and wilderness medicine training can help mitigate the fallout when injuries and illnesses do occur in remote settings.

But when we venture out into wilderness and engage in extreme activities, accidents can and do happen, sometimes the result of life-ending episodes. Unfortunately, we need to be prepared for that, too.

Gauging the Risk of Fatality

A quick check of the American Alpine Club’s periodical Accidents in North America Climbing shows that of 8,000-plus accidents covered over the more than 75 years the club has been gathering data, more than (more…)

Managing Mass Casualty Incidents in the Backcountry

Wilderness MedicineMost people think of wilderness medicine as providing medical care in a remote setting where access to conventional healthcare resources is limited or unavailable. They imagine someone treating a wound, applying a tourniquet, performing CPR, or fashioning a splint out of sticks and a bandana enabling a hiker with a broken leg to hobble to safety.

Few rarely consider the role of wilderness medicine in mass casualty events such as earthquakes, flash floods, wildfires, and other natural and manufactured disasters. These incidences result in multiple injuries that can overwhelm the resources available to treat the injured.

In the context of a mass casualty event, wilderness medicine providers fill all their traditional roles — caring for the injured and improvising to overcome the lack of medical equipment and supplies. However, their role often expands in scope as they face the challenges of assisting multiple patients at the same time suffering from diverse injuries.

Meeting this challenge requires knowledge of the system and resources available, along with an ability think and act quickly and rationally in order to triage patients. That means sorting and prioritizing patients on larger scale, based on the severity and urgency of their medical needs — again in the context of available resources.

Defining “Mass Casualty Incident”

A mass casualty incident (MCI) is any (more…)

A Fresh Look at Spinal Injury Care in the Backcountry

Wilderness MedicineIn wilderness medicine, the traditional response to a potential spinal injury has emphasized immobilizing the patient to prevent further injury. To this end, emergency responders have been trained to use advanced immobilization techniques and equipment, such as rigid cervical collars and spinal boards in conjunction with manual stabilization.

And while nobody educated in emergency medicine would argue against the importance of motion restriction, the priority is shifting as doctors and emergency personnel consider it in the larger context of overall patient health and safety.

Given the importance of the spine in a person’s overall health, the focus on immobilizing patients with suspected spinal injury is no surprise. The spine protects the spinal cord, which functions like a fiber-optic network to carry signals throughout the body to and from the brain. Interruptions in the continuity of the spinal cord can dramatically impact a person’s ability to move and to interpret and interact with the world.

However, over the last few decades, the medical community has acquired a vast body of evidence concerning care for a person with an obvious or potential spinal injury. As a result, recent years have seen a significant shift in thinking on this subject. The conversation regarding the extent to which a spinal injury is impacted by subsequent treatment and transport has evolved into a rather heated debate that’s (more…)

Wilderness Medicine: Accounting for Challenging Terrain

Wilderness MedicineWhen some hear the term “wilderness medicine,” they think of those rusty out-of-date First Aid kits that they used to carry with them on a personal hiking or camping trip. “As if that thing is going to do any good in an emergency.”

In fact, to the average summer weekend outdoor enthusiast, wilderness medicine is limited to treating minor cuts, scrapes, bruises, sprains, bites and poison ivy. A major tragedy would be the occasional broken bone. But it has always been much more than that.

To realize just how broad wilderness medicine really is, all you need to do is travel back to Antarctica in 1961. That’s when Russian explorer Leonid Rogozov suffered a severe case of appendicitis. Being the only medical doctor on site, he had to perform his own appendectomy. That’s among the extremes of what wilderness medicine is all about.

More recently, the Thailand cave rescue shined the spotlight on wilderness medicine. Thousands of rescue workers and medical personnel, including Thai Navy Seals, the national police, doctors, and nurses, rallied to save 12 teenagers and their soccer coach, all trapped in a complex cave system by floodwaters during a heavy rain. Rescuers had to locate and extract 13 people, some of whom couldn’t swim, from a flooded, two and a half mile stretch of caves.

The rescue tested experienced divers who struggled to navigate currents and squeeze through the narrow passages. Rescuers had to (more…)

SOAP Notes Keep Wilderness Medicine Clean

Wilderness MedicineIn the context of wilderness medicine, soap and SOAP are both indispensable. An explanation is in order. We’re all familiar with lower-case soap. This noun refers to a substance that’s added to water to remove dirt, grease, grime, and germs from various surfaces, including skin, hair, clothing, pots and pans, and so on.

Soap In The Wilderness

Traditional soap works in two ways — as a surfactant to break water tension, improving water’s ability to penetrate surfaces, and as a molecule that has a love-hate relationship with water. Soap molecules have two ends, one that’s hydrophilic (loves water) and the other that’s hydrophobic (hates water). The hydrophilic end binds to water, while the hydrophobic end binds to anything other than water — dirt, grease, grime, germs. Imagine soap molecules as tiny carabiners that shackle dirt molecules to water molecules to enable the water molecules to usher them away.

In backcountry and wilderness settings, soap plays a vital role in preventing infection and transmission of disease. In fact, scrubbing vigorously with soap and water may be among the most important risk-management technique you practice during your time in the wilderness.

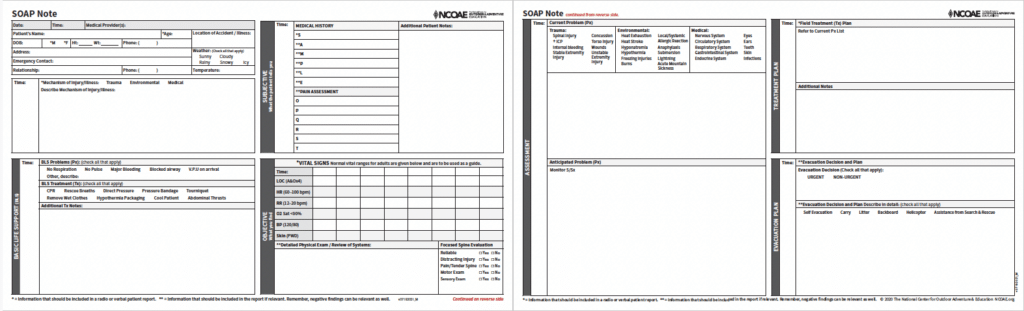

SOAP (Subjective, Objective, Assessment, Plan)

Now let’s move on to the other SOAP — all uppercase — which is an acronym for Subjective, Objective, Assessment, and Plan. As an outdoor educator, field instructor, or wilderness guide, this note-taking procedure is nearly as important as scrubbing your hands regularly with soap and water. This is especially true when you’re dealing with a client injury or illness in a remote setting.

SOAP Notes, which I’ll be covering in this post, separate important information from the chaos and fog of emotion in order to provide clean, uncluttered details for making informed medical decisions and emergency response plans.

With SOAP Notes in hand, field instructors and outdoor educators trained in wilderness medicine, as well as backcountry guides, are better prepared to respond to a medical emergency. They do this by:

- Following an organized, methodical process

- Tracking changes in a patient’s health status

- Keeping a record of assessments, anticipated problems, and any interventions already provided

- Communicating with emergency responders

- Ensuring a seamless transfer of patient care to next-level healthcare providers

- Documenting cases and care for improving organizational outcomes

Here at The National Center of Outdoor Adventure and Education (NCOAE), we developed the SOAP Note form shown below.

Our SOAP Note’s Form

Our SOAP Note form consists of the following seven sections (more…)

Let’s Add Humble to the 5 ‘Umbles’ of Hypothermia

Risk ManagementHypothermia is deadly. There, I said it! This potentially dangerous drop in body temperature is commonly defined as a core body temperature below 95 degrees Fahrenheit (35 degrees Celsius) after dropping from a healthy temperature of about 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit or 37 degrees Celsius.

The slightest variance from the “normal” range can disrupt the body’s ideal operating conditions, known as homeostasis. The negative impact of hypothermia on homeostasis is dramatic and therefore should not be underestimated. Hypothermic progression follows a path, moving first more slowly, then more rapidly toward non-movement and when properly treated, onto death.

Movement is life. Living things grow, evolve, learn and work to improve their circumstances. Non-living things hold fast to current circumstances unless acted upon by an outside force. As we’ve all experience, movement generates warmth, and this case, it combats hypothermia. A creature that has the appropriate amounts of items necessary for movement will generally maintain a body temperature conducive for life.

These items required for movement include nutrients, health, fitness, clothing, and sometimes technical outdoor tools such as an ice axe and crampons. A breakdown of these items leads to decreased movement and reduced temperature. In this post, we will look at the hypothermic process using the five umbles: (more…)

Heat Illness: Symptoms, Prevention, and Treatment

Medical TrainingNobody likes to be hot and sweaty on the trail. But when things turn from being uncomfortable to becoming downright dangerous, it’s time for quick, on-the-spot emergency action.

Heat illness is a range of medical conditions that result from the body’s inability to cope with an elevated heat load. When that occurs, it is more commonly referred to as “heat strain.” And whether you’re inactive in a warm, humid environment or participating in strenuous physical activity in the fall or winter, you are at an increased risk of heat illness.

For people who engage in backcountry adventures, heat illness and heat strain are among the many potential health and safety risks. That’s why our instructors at The National Center for Outdoor Adventure Education (NCOAE) include it in our Wilderness Medicine courses. In this post, we bring you up to speed on the basics, including the symptoms to watch for, preventive measures, and treatments to cool an overheated body.

From Bad to Worse on the Heat Illness Spectrum

Heat illness, heat strain, and related injuries occur when the core body temperature becomes elevated, stressing or surpassing the body’s ability to cool itself. Like a nuclear power plant, the human body can suffer serious and potentially fatal damage when its core becomes overheated.

The severity of the condition is on a spectrum generally divided into the following three levels: (more…)

Concussion Recognition and Treatment in the Backcountry

Wilderness Medicine TrainingConcussion recognition and treatment has gotten a lot of attention over the last decade, mostly in the context of youth and professional sports such as tackle football and soccer. It’s even a topic for those who serve in our armed forces. However, confusion over its prevention, diagnosis, and treatment remains widespread.

In an interview with a reporter from the Chicago Sun Times, former National Football League quarterback Brett Favre, who was knocked out cold only once in his 20-year career, claimed that “probably 90 percent” of the tackles he endured left him with a concussion.

He’s most likely correct in that estimation. After all, the definition of “concussion” is broad: “A concussion is a brain injury, a disturbance in brain function induced by traumatic forces, either from a direct blow to the head or a transmitted force from a blow to the body.” It disrupts brain function at the cellular metabolic level but does not result in major structural damage. Conventional MRI or CT scanning will not show evidence of a concussion.

So, how do you know if you or someone else has suffered a concussion while in the backcountry? And, after having made that determination, what should be done? Having clear answers to these two questions is essential for successful recovery and to prevent long-term cognitive and psychological complications. This is true no matter where the concussion takes place, but especially in the backcountry where medical treatment from a full-time team is unavailable. (more…)

TALK TO US

Have any further questions about our courses, what you’ll learn, or what else to expect? Contact us, we’re here to help!