When it comes to emergency medicine — whether in an urban setting or the backcountry — swift and accurate assessments play a pivotal role in determining the severity and progression of an injury and deciding the best course of action.

The decisions you make regarding treatment, evacuation, and transportation in cases of non-obvious threats to life and limb can determine not only whether someone lives or dies, but also their quality of life should they survive the emergency. After all, quality of life is a huge part of being alive. And a beating heart with minimal brain activity doesn’t always meet a person’s definition of “living.”

The National Center for Outdoor and Adventure Education (NCOAE) is a leading provider of wilderness medicine education and certification, and in this post, we’re taking the time to introduce you to the process of evaluating neurovascular function to determine the extent and progression of an injury. By doing so, you can make well-informed treatment, evacuation, and transportation decisions when responding to a medical emergency, no matter the origins of the incident.

Understanding What a Neurovascular Assessment Entails

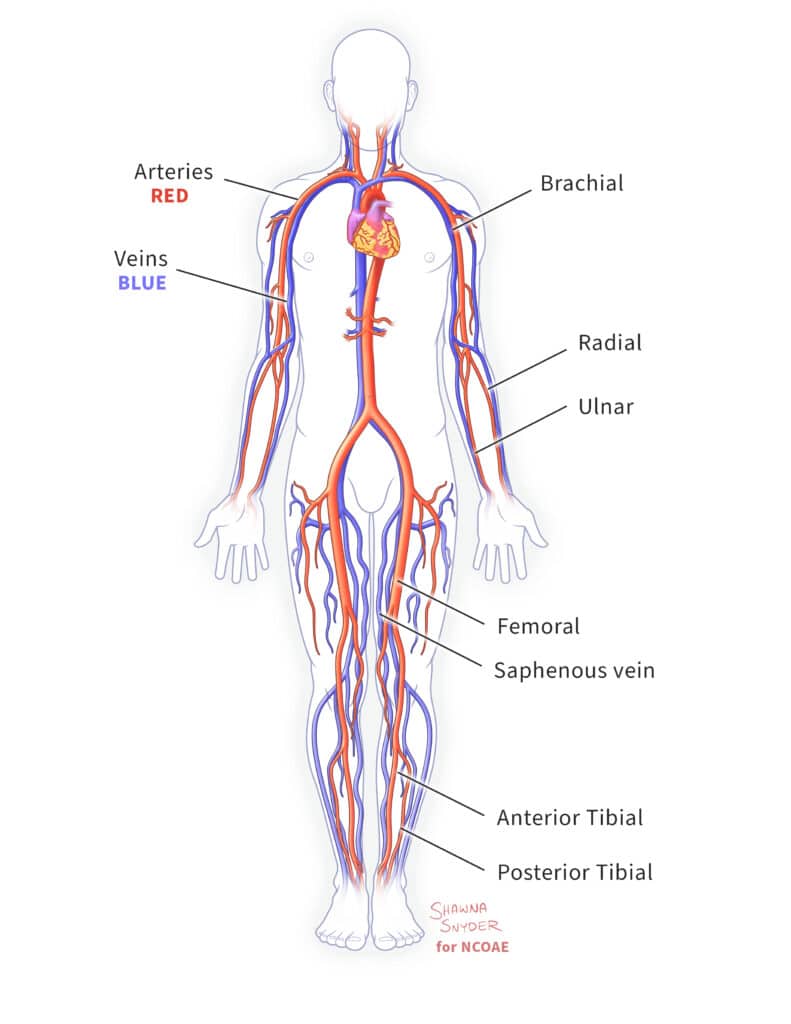

A neurovascular assessment is a collection of tests used by medical clinicians, including emergency medical personnel such as Wilderness First Responders and Wilderness EMTs, to determine whether someone is suffering nerve damage or impaired blood flow. Neuro refers to anything related to the body’s nervous system, and vascular refers to anything related to the body’s blood vessels. Neurovascular function encompasses the interplay between the brain, spinal cord, peripheral nerves, and blood vessels that supply oxygen and other vital nutrients to organs, limbs, and tissues. Any disruption of this intricate balance can lead to severe consequences ranging from impaired cognition to more severe conditions such as stroke or the loss of a limb.

Neurovascular status can be determined by simple tests of the following three functions:

- Circulation: Is blood circulating to the affected part of the body?

- Sensation: Does the patient have feeling in the affected part of the body?

- Motor: Can the patient move the affected part of the body?

These three functions are collectively referred to using the acronym CSM. For us, it does not stand for Command Sergeant Major, the ninth enlisted rank in the Army. Nor does it represent Certified Scrum Master, a technical designation for project managers. In wilderness medicine, CSM stands for Circulation, Sensation, and Motor.

Neurovascular assessment can be exceptionally detailed. However, in this post, we focus on three key indicators in each category of CSM to provide you with a total of nine specific neurological assessments.

Assessing Circulatory Function

Healthy circulatory function is essential to ensure sufficient blood supply to the brain, vital organs, limbs, and all cells and tissues of the body. Blood carries oxygen and other vital nutrients to cells, and it carries away carbon dioxide and other waste products. Too little blood flow can starve cells of vital nutrients and drown them in a pool of toxins. Excessive blood pressure around a muscle (compartment syndrome) can cause permanent damage or death.

Taking a person’s blood pressure is one way to evaluate circulatory function. However, in a wilderness setting, you may not have a blood pressure monitor at your disposal, which means you may need to evaluate circulation in respect to a specific body part. Here are three indicators to assess circulatory function in the field:

- Skin color: Normal pigmentation indicates healthy circulation. Skin that’s abnormally pale for the individual indicates impaired circulation. Abnormally dark or purple skin may indicate bruising or compartment syndrome.

- Skin temperature: If skin on one leg or arm (or hand or foot) is cooler than the other, the cooler extremity may have insufficient blood flow, or the other extremity may have excessive blood flow (as in the case of compartment syndrome).

- Pulse: A weak pulse may indicate a weak heart or blood vessel blockage. A pulse that is too strong may indicate high blood pressure, increased anxiety, or heart palpitations.

Assessing Sensation

Sensation is the perception of stimuli by the nervous system. Assessing sensation can help to identify abnormalities in nerve function and provide valuable insight into whether a person has suffered a spinal cord injury, nerve damage, or other neurological disorder. Abnormal sensations or a lack of sensation can help responders determine the best approach to evacuation and patient transport. Here are three useful indicators for assessing sensation:

- Pins/needles: The “pins and needles” sensation can indicate anything from a limb that has rested too long and “fallen asleep” due to a lack of blood flow, to a pinched nerve or other more serious neurological disorder. This sensation typically affects the extremities — arms, hands, legs, or feet.

- Numbness: Numbness is a partial or complete lack of sensation. If it is localized to a specific body part, it may indicate a pinched nerve or nerve damage. If it is more widespread, it could be related to injury of the brain or spinal column.

- Light touch and pin prick: Light touch assessment evaluates the ability of a person to perceive a soft object, such as a finger or a cotton swab, touching their skin. The pin prick assessment uses a pin or other pointy object to test a person’s ability to feel pain. Both assessments are crucial for identifying neurological issues such as peripheral nerve damage and spinal cord injuries.

Assessing Motor Function

Motor function is the ability to move and control one’s muscles. Motor function assessments can be very complex, evaluating strength, coordination, and reflexes. In wilderness medicine, however, the following three basic assessments can provide you with sufficient insight to decide on the best course of action:

- Paralysis: Inability to move.

- Free movement: The ability to move a limb or wiggle fingers or toes.

- Functional movement: Equal strength on both sides of one’s body or ability to move against resistance.

Using a Neurovascular Assessment to Decide the Best Course of Action

The simultaneous evaluation of circulation, sensation, and motor (CSM) function provides a comprehensive clinical picture that can shed light on the underlying cause of the medical emergency and help you determine the appropriate course of action. For example, suppose you are leading a small group on a backpacking expedition and you notice that a member of your group is struggling to keep pace. He’s limping, favoring his left leg, and complaining that his right shin hurts.

As a field instructor for the group, you have your Wilderness First Responder (WFR) designation, so you know to perform a neurovascular assessment. You determine that circulation and sensation are normal in his right leg, but that its functional movement is impaired primarily due to the pain. Upon further exploration, you learn that the participant was running a great deal in preparation for their backcountry expedition. Based on all the evidence, you determine the underlying cause is probably shin splints. Your participant simply needs to wrap the right leg below the knee and take more frequent rests until you reach a location where the hiker can be safely transported home.

In contrast, if the participant had complained of sudden weakness on one side of his body accompanied by altered sensation and a rapid, weak pulse, you may have concluded a stroke or other vascular event had occurred, this requiring immediate evacuation and transportation to a hospital. Or, had the participant experienced bilateral weakness, numbness, and an altered mental status, you might conclude that he was suffering from low sugar or exposure to a toxin, which would require other interventions.

Keep this in mind: Regardless of the medical emergency, the more information and insight you have into the nature of the emergency and its underlying cause, the better your decisions are likely to be and the better the outcome. Performing a neurovascular assessment takes seconds and can significantly reduce the risks to life and limb.

For additional guidance on how to respond to a medical emergency, see our previous post, “Six Tips on How Best to Respond to a Medical Emergency.”

For additional guidance and practice, we encourage you to enroll in a The National Center for Outdoor & Adventure Education’s (NCOAE’s) Emergency Medicine Course or Wilderness Medicine Course.

– – – – – – –

About the Author: Todd Mullenix is the Director of Wilderness Medicine Education at The National Center for Outdoor & Adventure Education in Wilmington, North Carolina.

TALK TO US

Have any further questions about our courses, what you’ll learn, or what else to expect? Contact us, we’re here to help!

Leave a comment