Language provides a foundation for human progress. Having a common language enables us to communicate, collaborate, and coordinate our efforts in able us to achieve more together than any of us could possibly achieve on our own. It allows us to organize our thoughts and solve problems collectively.

It’s when we’re not speaking the same language, or we have a different understanding of the terminology being used, that chaos ensues. Take NASA’s Mars Climate Orbiter (aka Mars Surveyor ’98 Orbiter), for example. Launched on December 11, 1998, the spacecraft was lost because NASA used the International System of Units (metric), while the company that built the spacecraft, Lockheed Martin, used the United States customary units (imperial). That simple miscommunication caused the Mars Climate Orbiter to enter the Martian atmosphere on September 23, 1999, at the wrong angle and disintegrate.

As practitioners of wilderness medicine, outdoor educators and others can learn valuable lessons from that story. After all, successful treatment outcomes often require close communication, collaboration, and coordination among treatment providers. Having a different understanding of the same terminology can result in serious negative consequences. This is especially true in life-threatening situations where the space between life and death can be as narrow as a razor’s edge. In these situations, using a common language can save lives.

In this post, we explore wilderness medicine terminology that’s a common source of misunderstandings. By increasing your awareness of how these terms are often used and understood, you can ensure that you and other members of the treatment team are communicating clearly and precisely.

Recognizing Terms That Can Be a Source of Confusion

Communication is so important that EMT textbooks often include an entire chapter or appendix on medical terminology. These terms and their definitions ensure clarity on everything from ; colors (for example, cyano for “dark blue” and erythron for “red”) to directional terms (such as proximal for “close to” and distal for “far from”) and anatomical terms (such as prone for “face down” and supine for “face up.”)

To enable healthcare providers to communicate more efficiently without confusion, many state offices of Emergency Medical Services have lists of approved acronyms. For example, some hospitals and institutions prohibit the use of MS in reference to “morphine sulfate” to avoid confusion with the more common use of MS in reference to “multiple sclerosis.” They may require that “morphine sulfate” be spelled out or abbreviated as “MS Sulfate” or “MSO4.”

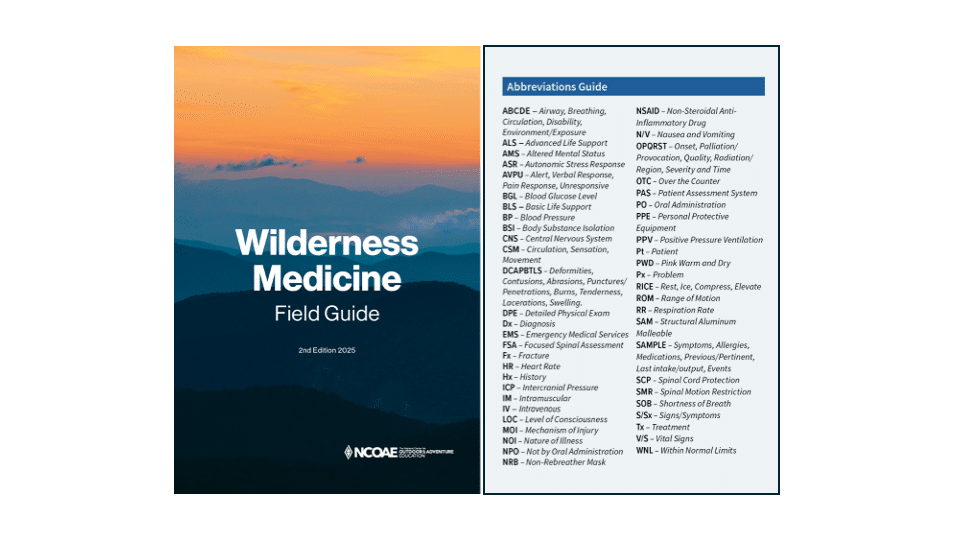

Our own National Center for Outdoor Adventure and Education (NCOAE) Wilderness Medicine Field Guide provides an abbreviation guide to clarify use of acronyms such as CSM for “Circulation, Sensation, and Movement” and differentiate it from the military abbreviation for “Command Sergeant Major.”

NSAIDS is a common abbreviation for “non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs” such ibuprofen and naproxen, but this acronym is also used as a mnemonic for remembering how to conduct a focused spine assessment (FSA):

- Neuro complaints/exam normal?

- Sixty-five years or older?

- Altered?

- Intoxicated?

- Distracting injury?

- Spine pain or tenderness?

BLS refers to “basic life support,” which almost universally includes any care that is not advanced life support (ALS). BLS includes cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), use of an automated external defibrillator (AED), basic airway management, control of bleeding, basic first aid, and other non-invasive treatments. However, the line between BLS and ALS blurs for the Wilderness EMT when, in some states, EMTs are allowed to perform intravenous (IV) vascular access — a more invasive procedure.

CPR is often used synonymously with “chest compressions.” For example, EMTs are commonly instructed during a cardiac arrest to begin CPR immediately after delivering a shock from an AED. It may be more accurate to instruct EMTs to “resume compressions” after delivering the shock when the breathing part of CPR is to be delayed.

The “breaths” that we refer to during CPR are not so different from the “breaths” we give during rescue breathing, but the application changes and requires some amount of clarity when choreographing the tasks during an emergency. The very term “rescue breathing” is most specifically related to “ventilating” (breathing for) a patient who still has a pulse, but these terms are often used interchangeably during cardiac arrest.

The term “bagging” is nearly universally used when talking about giving breaths (ventilating a patient), but “bagging” isn’t the best term to use when family members are present, as they often misinterpret it as a reference to a body bag, which can be very upsetting.

Causes of altered mental status (AMS) can be remembered with the mnemonic AEIOUTIPS, which begins with Alcohol, Epilepsy and Infection. How then do we abbreviate Acute Mountain Sickness? Can someone get AMS from AMS?

Even the meaning of words related to the people we help in distress are open to interpretation. The term “victim,” for example, most commonly refers to a legal status of a person having suffered harm from a perpetrator of a crime. That definition makes it a poor choice for referring to someone who has suffered an accident or become ill in a wilderness setting. In such cases, “patient” or “subject” may be more accurate.

The word “shock” is another term that commonly causes confusion in medicine. It may refer to the emotional state of distress resulting from a traumatic event, the physical state of inadequate tissue perfusion of oxygen throughout the body, or the act of delivering an electrical shock to the body using an AED. At the ALS level, there are other therapeutic uses of electrical “shocks” to help patients, so being specific about the type of shock being called for is often important.

The term “drowning” has long been used to refer only to the death caused by going under water. This term however should be used to discuss any respiratory distress, failure, or arrest caused by exposure to a liquid including as it relates to those who survive a drowning.

The “rule of palms” is a method of using the patient’s entire hand to estimate one percent of their body surface area burns. The term is actually a misnomer, because the entire hand, not just the palm, is used to make the estimate.

A “heart attack” is a lack of blood flow to the heart muscle due to a blockage in a coronary artery. The term is commonly used synonymously with “sudden cardiac arrest,” which may or may not ultimately be the cause of the death.

A “stroke” is a “brain attack” and is most commonly a reduction of blood flow to the brain due to a clot. The term “heatstroke” is not a stroke at all; it describes the body’s failure to dissipate heat sufficiently in an excessively.

These are only a handful of the many medical terms and acronyms that can lead to misunderstandings.

Learning the Language of Emergency Medicine

In emergency medicine, specialized terminology enables us to communicate effectively and efficiently with other members of the treatment team. But it only works if we all use the same terminology consistently and have a shared understanding of what specific terms and acronyms mean.

To enhance your ability to provide the best possible chances of positive outcomes for your wilderness medicine patients, we strongly encourage you to study the terminology and practice using it during your EMT training. Saving lives involves more than merely assessing and treating patients; it often requires teamwork. So, learn the language — stat! (And that term is an abbreviation of the Latin word statim, which means “immediately.”)

Words Matter!

Here at NCOAE, we offer several in-depth, hands-on courses in wilderness medicine, all of which include learning and practicing the language used in the field. You can check out our wilderness medicine course offerings by visiting ncoae.org/wilderness-medicine.

– – – – – – –

About the Author: Todd Mullenix is the Director of Wilderness Medicine Education at The National Center for Outdoor & Adventure Education (NCOAE) in Wilmington, North Carolina.

TALK TO US

Have any further questions about our courses, what you’ll learn, or what else to expect? Contact us, we’re here to help!

Leave a comment