Safety in the Backcountry: Deciding When to Bail on a Trip or Adventure

December 03, 2025

“What matters most is how well you walk through the fire.” ~ Charles Bukowski

When it comes to just about every worthwhile pursuit, the more you put into it, the more you get out. In the context of human-powered outdoor adventures, especially those that test your metal, that means pushing the limits and, for those of us who are thrill-seekers, risking life and limb.

Spending time in the backcountry is often more than simply experiencing the great outdoors; it often entails exposing ourselves to, and overcoming, adversity. Through the process, we hone our outdoor skills and build strength, coordination, and character.

Part of the attraction and much of the fun we experience when we engage in extreme outdoor activities such as mountaineering, whitewater rafting/kayaking, rock climbing, skiing, snowboarding, and so on, is the thrill. We choose to expose ourselves to an increased risk of injury or death, because that’s part of what makes extreme sports so much fun.

The secret to success is managing risk and adversity so an outing becomes a thrilling challenge while still preserving life and limb. While we crave an epic adventure that we can live to remember and talk about, achieving the right balance often involves deciding when to bail; when the balance between risk and reward is weighted far too heavily on the side of risk.

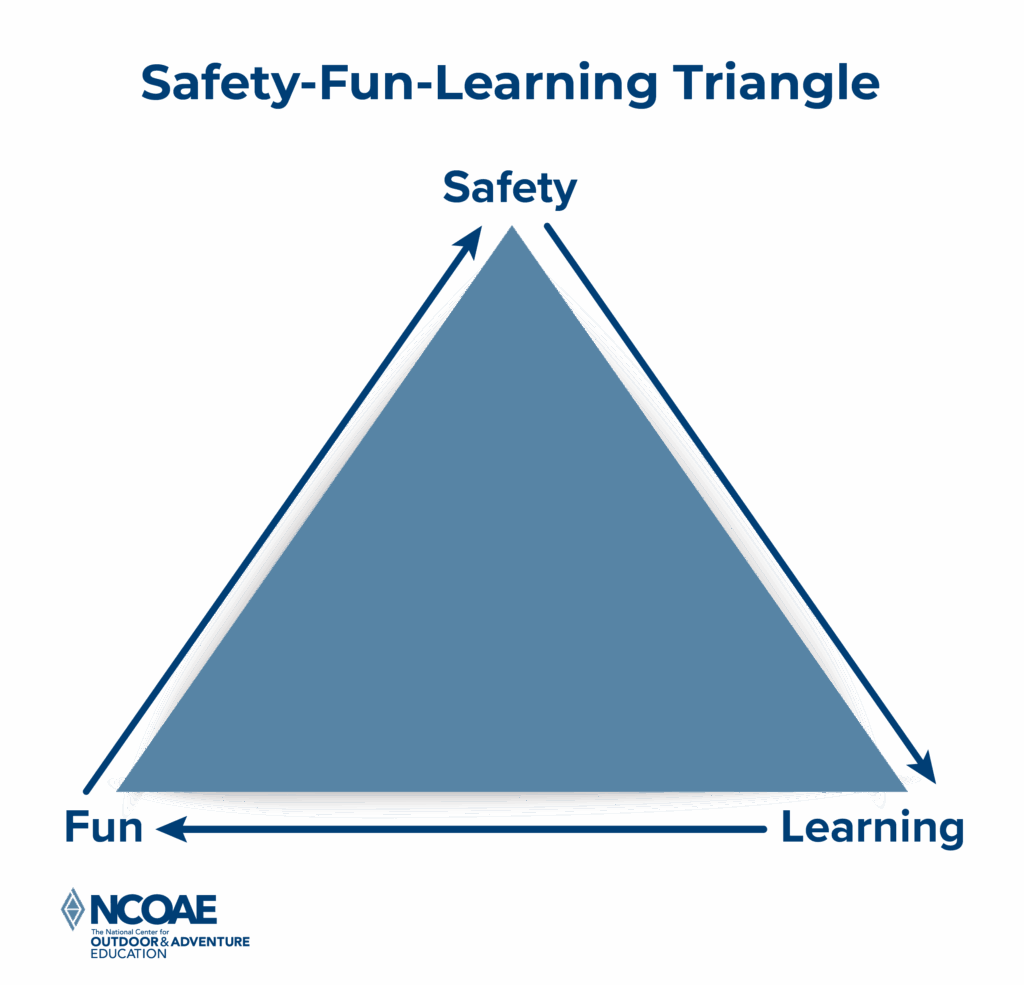

Here at The National Center for Outdoor & Adventure Education (NCOAE), we recommend using the following Safety-Fun-Learning Triangle as a guide to achieving the right balance:

Pre-Trip Bailing

It’s late on a Friday night and the floor is littered with maps, satellite images, weather reports and info I received from reputable sources.

Teeming with excitement, my brain narrows in on the largest, wildest expedition I can put together with the info in front of me. As the early morning hours of the next day approach, I have pared down my list to one or two realistic options (realistic for me).

Regardless of whether I am consciously aware of it, this trip planning I routinely engage in almost always involves pre-trip bailing. I start with “visions of grandeur” — my dream scenarios — and then refine my planning based on what I deem to be realistic. As I sift through my information and resources, I bail on the expeditions that have too many unanswered questions, too many what-ifs, too many places to disappear, get stuck, or die. Better to bail on a potentially terrible experience before heading out, especially when planning a solo adventure.

At-the-Trailhead Bailing

Rain, sleet, snow, or howling wind won’t turn me around at a trailhead. That’s because I planned and came prepared. Even if I know I’m facing some nasty weather for an entire week, I go. I know it’s going to be tough, possibly depressing at times, but I also know that when I make it through to the other side, how rewarding it will be!

(Photo credit: © Stephen Mullaney)

So, what will make me bail at the trailhead?

- Major change in conditions: Avalanche, flash flood, active shooter in the backcountry (yes, this is a condition that has made me bail).

- Area closure: Areas may be closed for all sorts of reasons; for example, hurricane Helene in North Carolina, tropical depression Chantal in the Piedmont area of North Carolina, various forest fires and government shutdowns.

- How I’m feeling: Feeling sick or injured, or realizing situations at the trailhead aren’t what I planned, for can prompt me to bail.

However, quitting at the trailhead doesn’t always mean bailing altogether. There’s always my Plan B, which allows me to bail in style and spend quality time in the wild. Plan B is usually the same activity in a different location or, with a little shuffling of the deck, maybe coming up with a shorter or less intense route at the planned location.

Having a Plan B is a bit more challenging on backcountry ski trips or whitewater paddling trips, especially if you are already on the river, but with a little flexibility, you can usually create and execute a Plan B.

Bailing During a Solo Expedition

Bailing during an expedition can be even more difficult because you have more skin in the game and need to invest additional effort in planning and executing your bailout. But here are some conditions that might cause me to bail out when I’m on a solo expedition:

- I am facing something that makes me completely stop and wonder, “What the hell am I doing here?”

- I am pushing beyond my normal skillset and digging into skills rarely used, or I’m attempting to use skills and knowledge I have never used before.

- I start improvising with my equipment to keep myself safe or maintain an illusion of safety.

- I start to feel as though I am on the verge of becoming the focus of an incident or accident report.

- I notice I am immersed in a loop of “what-ifs.”

Consider bailing when facing dangerous conditions such as severe weather, lack of water or food, significant injury or illness, or losing daylight. Also consider turning around if the terrain becomes too challenging or unfamiliar, you’re physically and mentally exhausted, you have a strong gut feeling of danger from encounters, or your gear is inadequate for changing conditions.

There is no shame in bailing: I have eddied out of rapids knowing that conditions were not favorable for me to return home uninjured or alive. I carried my boat and gear miles through a dense forest to the closest road I could find. I was embarrassed, but I had no good reason to be. I am alive and well, and that is what counts. In situations like these, you need to think clearly, make your bail plan, and stick to it. Bailing is a sign of maturity and self-awareness, not failure, because it’s essential for ensuring that you make it through a potential crisis.

Deciding to Bail When Guiding a Group

The decision to bail often depends, in part, on whether you’re alone or leading a group. When I am engaging in high-risk activities on my own, I push myself far closer to the edge than I would ever take a client, friend, or group. When I’m guiding a group, I find it much easier to decide to pull the cord when conditions warrant it. I start by asking myself, “Can I return everyone home better than when they set out with me?”

“Better” for me usually means “bruised but not broken.” I want to lead the group on a memorable, transformative adventure without any severe injuries or fatalities. Bumped, bruised, dirty, and tired is okay, so long as everyone can tell their story over drinks with friends instead over a coffin or from a hospital bed.

Unfortunately, in a group setting, some people get summit fever and want to continue no matter what. “I paid for you to get me down river/to the top/to complete the traverse” is a common complaint outdoor adventure guides hear.

(Photo credit: © Stephen Mullaney)

Many years ago, I was guiding a river trip, accompanied by two other guides. We pulled over and got off the river with the group to hike to a beautiful lunch spot. After lunch, we returned to the boats and a river that was five or six feet higher and rising rapidly. We knew that most of our clients did not have the experience to get down river without flipping. And in those conditions, anyone ending up in the water would be exposed to every hazard on the river. There was a high possibility of severe injury or death.

We radioed out to our support staff and told them to bring a van to a road where we could hike out and meet up.

When we shared our plan with the group, one individual became very upset. He said he had paid for a river trip and that we would not bail out if we were on our own personal trip.

He was right about everything he said, and I told him so. But I finished with one important detail, “This is not my personal trip. I have no desire to have to call loved ones to tell them I made a poor decision and there were consequences.”

He hiked out with the group. My guides and I rafted up the canoes and paddled to the take-out.

Guiding means leaning into difficult situations and making difficult decisions. Guiding puts you in a space that few people ever experience — life and death decision-making. Lean into safety. When you are feeling unsafe, so is your group or client, and you have a clear sign to bail!

I once was told, “There are old mountaineers and bold mountaineers, but there are no old, bold mountaineers.” The takeaway here is to make the tough call and bail whenever life or limb is at considerable risk and then come back when conditions are right.

Another quote I learned when sailing across the Irish sea was, “Old sailors reef first.” To reef is to reduce the amount of sail area on your boat. It means going slower with more control. If you wait too long to reef the sails, you put your boat and everyone on it at risk of destruction and death.

Safety is your job. It’s everyone’s job. So never hesitate to bail when the level of risk warrants it.

Bailing Is a Skill You Need to Practice

My wife and daughter joke that I return home, even after the smallest outing, “Muddy, bloody and thirsty.” They are right. Even on day hikes I plan routes I have never attempted and am fairly certain that nobody else has either. I love traveling off trail to find elements of the landscape that I have not interacted with before. I seek unknown landscapes, unknown paths, and unknown outcomes. In the process, I often bail when I encounter potentially dangerous conditions or find myself in precarious situations. I then return home with a giant smile on my face and the inspiration to go further and farther next time.

Pro Tip: Bailing does not mean you lack skills, knowledge, or experience. To the contrary, bailing is using your skills, knowledge, and experience to find a worthy challenge and deciding to put it off for another day when conditions are more conducive to your success.

There is no scale of when to call it quits. It is a skill you develop through practice. I encourage you push the limits and engage in activities that are outside your comfort zone, but also to practice bailing on purpose when you see your objective right in front of you. Feel the disappointment and embarrassment as you test your decision-making skills and shift the balance between risk and reward toward greater levels of safety. This may not feel great in the moment, but it will improve your ability to decide when to bail (and when not to).

Just as you test your gear before a trip, conduct an honest evaluation of your knowledge, skills, and experience (and limitations) and practice being calm in situations that seem dangerous. Practice, practice, practice.

Walking through the fire requires coming out of it safely on the other side.

– – – – – – –

About the Author: Stephen Mullaney is the Director of School Partnerships and Staff Development at The National Center for Outdoor & Adventure Education (NCOAE).

TALK TO US

Have any further questions about our courses, what you’ll learn, or what else to expect? Contact us, we’re here to help!

Leave a comment