In the safety and comfort of the modern world, we often forget that the natural world can be a dangerous, unforgiving, and uncaring place. For many of us who love wilderness and the backcountry, that’s large part of its attraction.

We choose to explore areas where some fear to go, and we participate in activities that may straddle the line between the safe and perilous. But we do so, backed by best practices and training in wilderness risk management.

Mountaineering, rock climbing, and whitewater rafting can be dangerous undertakings, but even a leisurely hike through the backcountry carries risk. Wilderness emergency examples include entering an area teaming with unpredictable wildlife, crossing paths with a venomous snake, getting swept up in a flash flood, or encountering other unpredictable dangers.

Here at The National Center for Outdoor & Adventure Education (NCOAE), we take many precautions to mitigate the risks. Education, training, planning, and preparation can all limit the risk of injuries and preventable illnesses, and wilderness medicine training can help mitigate the fallout when injuries and illnesses do occur in remote settings.

But when we venture out into wilderness and engage in extreme activities, accidents can and do happen, sometimes the result of life-ending episodes. Unfortunately, we need to be prepared for that, too.

Gauging the Risk of Fatality

A quick check of the American Alpine Club’s periodical Accidents in North America Climbing shows that of 8,000-plus accidents covered over the more than 75 years the club has been gathering data, more than 1,700 resulted in fatalities. That’s 20 percent of documented climbing accidents in North America.

Within nearly the same period (1950–2020), American Whitewater, a nonprofit that seeks to conserve and restore waterways and enhance whitewater safety, reports 1,985 fatalities involving whitewater rafting, kayaking, canoeing, and other watercraft.

I’m not trying to scare you off from engaging in your favorite wilderness activities, nor am I offering your parents and grandparents more ammunition to discourage your participation. I’m also not exaggerating the level of risk. Most certainly, the vast majority of wilderness excursions have positive outcomes. And, of course, the benefits far outweigh the risks.

I’m citing these statistics only to point out that accidents happen, fatalities do occur, and despite the fact that wilderness medicine focuses primarily on positive outcomes, we don’t always achieve our objective. And we need to be prepared well ahead of time for that possibility.

Understanding the Grieving Process

In her book On Death and Dying, Elisabeth Kubler-Ross explains that, in response to the death of someone close to us, we proceed through five stages of grief:

- Denial

- Anger

- Bargaining

- Depression

- Acceptance

This process isn’t necessarily linear; nor does it follow any fixed timeline. But it shows that the loss of someone close to us, such as a wilderness partner, is a traumatic event, one that affects us deeply, emotionally and psychologically, and it can take considerable time to recover.

However, in a wilderness setting, we lack the time and mental space to grieve. As a result, this five-stage process can become compressed and more erratic, magnifying the trauma of the loss. Although this trauma may not be manifested physically, it is a trauma that we, as practitioners of wilderness medicine, must account for and be prepared to enable ourselves and others to deal with effectively.

Accounting for Grief When Sizing Up the Scene

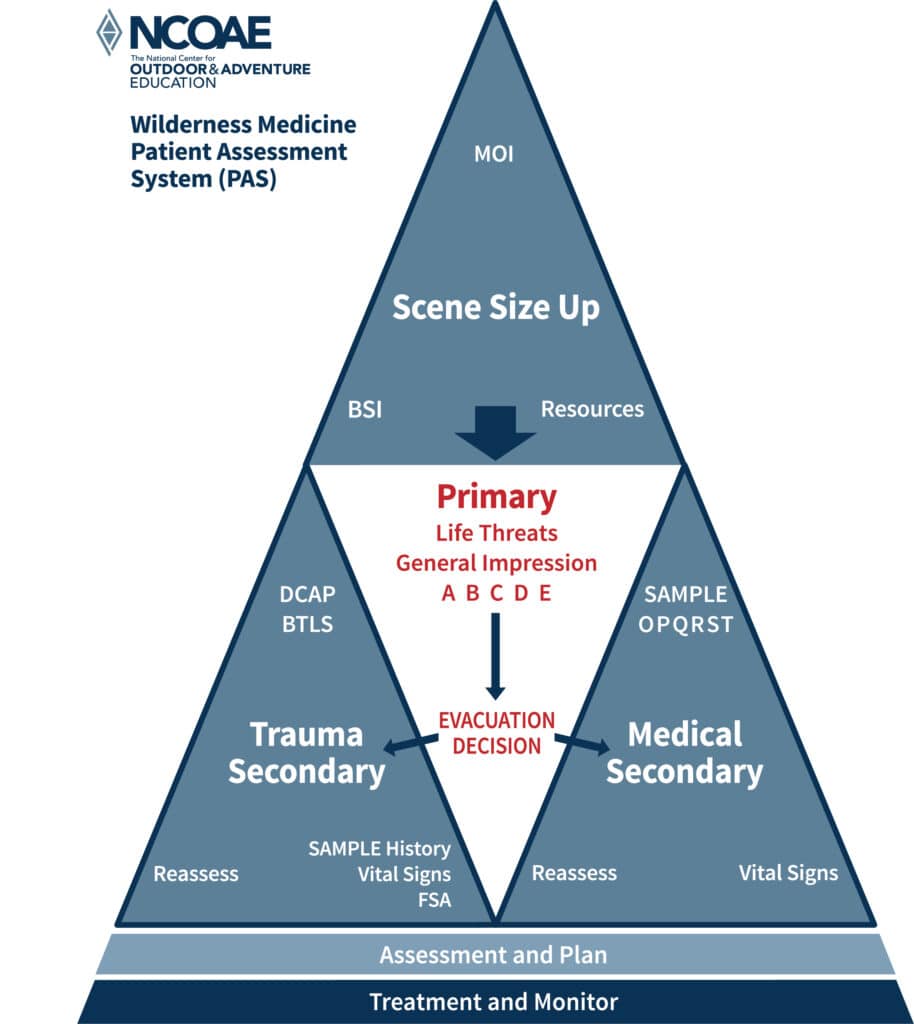

As I pointed out in last week’s post, “Managing Mass Casualty Incidents in the Backcountry,” one of your responsibilities as a first responder is to bring order to the chaos. You begin this process by sizing up the scene. Here at NCOAE, we use the Scene Size Up triangle shown below as a quick reference:

If you’re unfamiliar with the Scene Size Up triangle, here’s what you need to know:

- Evaluate the mechanism of injury (MOI). The MOI can provide valuable insight into the appropriate treatment/response.

- Attend to body substance isolation (BSI) and take inventory of available resources. Protect yourself by washing your hands; using gloves, eyewear, a face mask; and properly disposing of soiled bandages, dressings, and clothing. Also, take stock of the medical equipment and supplies you have and the human resources available that can help you respond effectively.

- Perform a Primary ABCDE assessment (Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, and Exposure).

- Based on the results of your Primary assessment, perform a secondary Trauma or Medical assessment:

- Trauma assessment: Use DCAP (Deformities, Contusions, Abrasions, Punctures) and BTLS (Burns, Tenderness, Lacerations, Swelling) to evaluate for traumatic injuries.

- Medical assessment: Use the OPQRST assessment method (Onset, Provocation, Quality, Radiation, Severity, and Time) to evaluate for illnesses.

- Continue to reassess the patient. Patient assessment may include SAMPLE (Symptoms, Allergies, Medications, Pertinent history, Last intake/output, Events); vital signs; and FSA (Focused Spine Assessment).

- Develop an overall assessment and treatment/evacuation plan.

- Implement the treatment/evacuation plan while continuing to monitor the patient’s condition.

In most cases, sizing up the scene involves one patient, but when a patient is suffering from a severe injury or illness — or has died — the situation can elicit a strong emotional response from other members of the group. This response must be managed to prevent the already horrible situation from worsening. Those who are struggling with the loss become your patients, too. And one of those might be yourself.

Providing Psychological First Aid

Psychological first aid (PFA) consists of methods for bringing a sense of healing and recovery in the event of a mental crisis. While these methods vary greatly and are endless in scope, PSA for wilderness medicine can initially focus on ways to reduce additional harm while moving the patient to a place where definitive healing can occur.

In a wilderness setting connected to a fatality, this process may include the following:

- Safety: Instill a sense of safety by addressing the cause of the death and communicating the actions taken to reduce threats to the remaining group.

- Calm: Create a sense of calm by speaking quietly and thoughtfully about the realities of the situation and possible solutions.

- Self-care: Provide opportunities for the patient to take an active role in focusing on making their immediate situation better through nourishment, comfort, and communication.

- Community: Reconnect the patient with the group and establish group tasks intended to improve the situation.

- Hope: Help maintain the patient’s hopefulness by accomplishing small goals as part of an understood, realistic path toward a desired outcome.

“The mountains are calling and I must go,” wrote John Muir. In response, Dee Molenaar, an American mountaineer who lived to be 101, reminds us that the mountains don’t care, but we do.

Whenever we venture from the relative safety of our homes into the wilderness and whenever we engage in activities that put our safety at risk, we do so with the hope that our adventure will enrich our lives in some way and that everyone in our party returns with life and limbs intact.

However, we enter the wilderness with eyes wide open, knowing that bad things can happen. Being prepared for such eventualities empowers us to cope more effectively with them and recover more quickly from them, restoring a sense of calm without losing our love for the wilderness and our drive to live life fully.

Learn everything you need to know about wilderness medicine by taking our training course.

– – – – – – –

About the Author: Todd Mullenix is the Director of Wilderness Medicine Education at The National Center for Outdoor & Adventure Education in Wilmington, North Carolina.

TALK TO US

Have any further questions about our courses, what you’ll learn, or what else to expect? Contact us, we’re here to help!

Leave a comment